Sanja Kulenovic and her new husband were celebrating their honeymoon in Pasadena, California, in 1992 when they turned on CNN to discover their hometown, Sarajevo, being devastated by bombing. As the nation of Yugoslavia collapsed, Sanja and her husband became people without a country, but their primary concern was their family and loved ones back home. How were they doing? What was happening to them as the city was sieged? Would they survive?

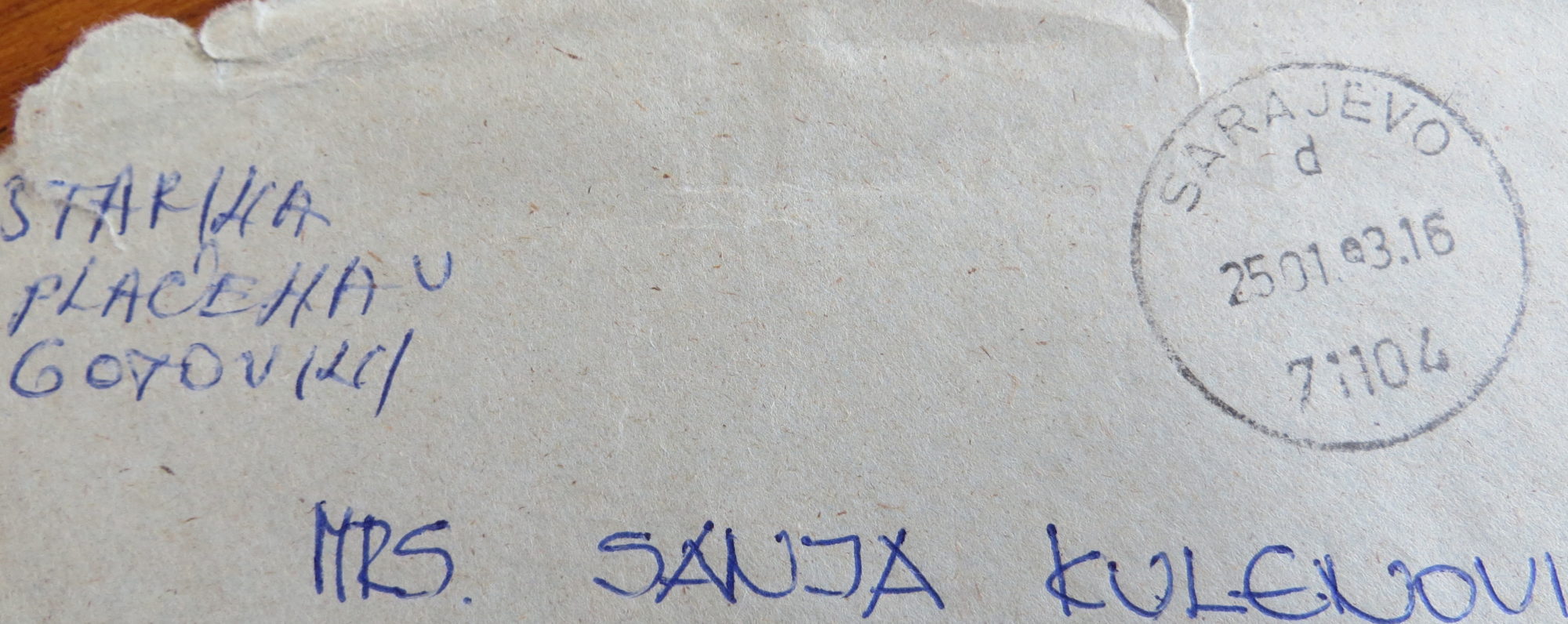

Sanja recounts her and her husband’s efforts to build a new life as refugees in Southern California, finding joy in securing a pizza-delivery job and receiving letters or brief phone calls from Sarajevo. Those letters—often written in darkness as bombs fell and gunfire rang out—vividly capture the suffering Sanja’s family and other Sarajevans endured through almost four years of daily bombardments, the perpetual threat of sniper fire, and three frozen, foodless winters.

The Siege of Sarajevo illustrates the human toll of war and the highly personal consequences of what often seem like faraway conflicts. The book is also a tribute to the resilience of the human spirit, reminding readers that they—like Sanja and her family—are stronger than they ever imagined.

Reviews

Blending personal experiences, letters, and news stories, Sanja Kulenovic’s memoir captures courage and resilience during the danger and displacement of Sarajevo in the 1990s.

While honeymooning in Southern California in 1992, Sanja and her husband Djeno became refugees when violence erupted in their beloved hometown. Over 1,425 days, “the longest siege of any city in modern history,” shelling and sniper fire left 11,541 dead and 60% of the city’s homes uninhabitable.

The couple had to start from scratch. They rebuilt their lives in an alien culture in a remarkable way, raising a family, undertaking graduate studies, starting careers. They realized early on, though, that they were the lucky ones. Within the memoir, their personal struggles take a backseat to events in Bosnia. Contact with loved ones is established; details of the madness heaped upon Sarajevo becomes known.

Of Muslim heritage but raised in a mixed Sarajevan culture that “perceived people as good or bad based on values other than ethnicity or religion,” Kulenovic does not linger on factions, ethnic groups, or nationalistic movements, but rather focuses on the human toll of genocide and urbicide.

Perhaps the most revealing bits of the book are contained in letters from Kulenovic’s parents and siblings. As the bombs fall, her father reveals an ingenious recipe for making mayonnaise with powdered milk. Her mother writes of using hard, sour beans from a relief agency as fuel in the family stove—and also that she often hears herself saying, “Thank God.” The family is captured as “composed, dignified, and proud human beings … even with their lives reduced to bare survival.”

The book ends with the Kulenovics’ emotional return to Sarajevo, the once-cultured capital city rising from the rubble. The Siege of Sarajevo memorializes a time of suffering and survival and shines a light on immigration crises everywhere.

JOE TAYLOR (September / October 2019)

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The author of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the author for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.

By Zoran Stevanovic, UNHCR Central Europe:

It’s a difficult task to read books written by close friends. There is always some uneasiness about it, certain fear and apprehension—it sometimes lasts for only a few pages, sometimes through a good part of the book. Sometimes it never leaves you. What if I don’t like it? How do I answer that all important question posed by a friend author: “What do you think about my book?”

Well, your book surprised me in more than one way and I like it much more than I had expected. The fact that I couldn’t put it down and then couldn’t sleep for the rest of the night is another story.

To be honest, what I had expected was some sort of historical narrative, a “one way” communication, if you will, document based on war events and dry facts, and not so much of you in it. What I found is the opposite: feelings, thoughts and emotions—state of mind of my friend Sanja.

You managed to carry the idea of a “Sarajevan” throughout the book masterfully. I love that this idea did not come from our arrogant and ignorant view that anyone who is not from Sarajevo is not worthy, the view I had before the war, I admit. In your book, “Sarajevan” is still an institution, a mentality, a way of life, humorous and perhaps cynical at the same time—but definitely not one that puts us above everyone else. This idea is obvious and important in parts of the book where you describe life under siege—theatre performances in freezing Opera house, classrooms in shelters, weddings under sniper fire, jokes and parties…resilience, dignity and strength to carry on.

I particularly like the narrative where Nadia and Leila are described as Americans—rightly so—but at the same time undoubtedly and firmly connected to Sarajevo: they both ask to go every summer to visit (even though Nana’s house doesn’t have Wifi), have their favorite cevapi place in town, and Leila’s phone case features Bosnian flag. But, at the same time, they still do not understand, nor they care about, ethnic structure of the city and backgrounds of Bosnians they know, just like we didn’t when we lived there.

I love that the reader is taken back to Sarajevo after the war, with your return to work for Parsons there.

But most of all, I love the last section of the book, the last page. I think it’s an ideal way to finish the story. Gentle, filled with love, it’s a sign, a hidden message, not only for your girls, but for the whole new generation of Bosnians connected to Sarajevo one way or the other—to their parents, friends and family.

Be proud of your work. Your book is interesting, emotional, strong, even to us who very well know what you wrote about. This book is not only for Nadia and Leila, for close friends and their children. This book is a wonderful and important story for all, for audience much larger than you anticipated. And that is the best thing about it. For that, you have my utmost respect.

By Paige Martini, Editor:

In her book, Sanja chronicles the harrowing experiences of her family and friends who are trapped in Sarajevo, as well as the monotonous torture of helplessly watching the violence rage from afar. She is a thorough historian, and has painstakingly collected and translated dozens of letters she received from family and friends throughout the conflict; an incredible feat considering how near-impossible it was to communicate either in or out of Sarajevo during the siege. The rarity of these letters alone makes her memoir not only a profound reflection on the suffering human beings are capable of enduring, but an invaluable historical archive of the longest siege on a capital city in the history of modern warfare.

Importantly, Sanja chooses not to reflect on the identity of the conflict’s aggressors in her memoir. It would be easy to lash out with bitterness at those who caused her family, friends and fellow Sarajevans so much suffering. Instead, Sanja uses her platform to commemorate and celebrate the tenacious shared humanity of all Sarajevans who lived and died in the conflict.

Sanja’s story is at once sickening and beautiful; horrifying yet hopeful. In times such as these, we need stories like this. It has become too easy to reduce the volume of human suffering to a statistic on a screen. The Siege of Sarajevobegs us not to forget what happened to the people of Sarajevo- to each individual, unique, human person who lived or died during the siege. Hers is a story that will live with you.