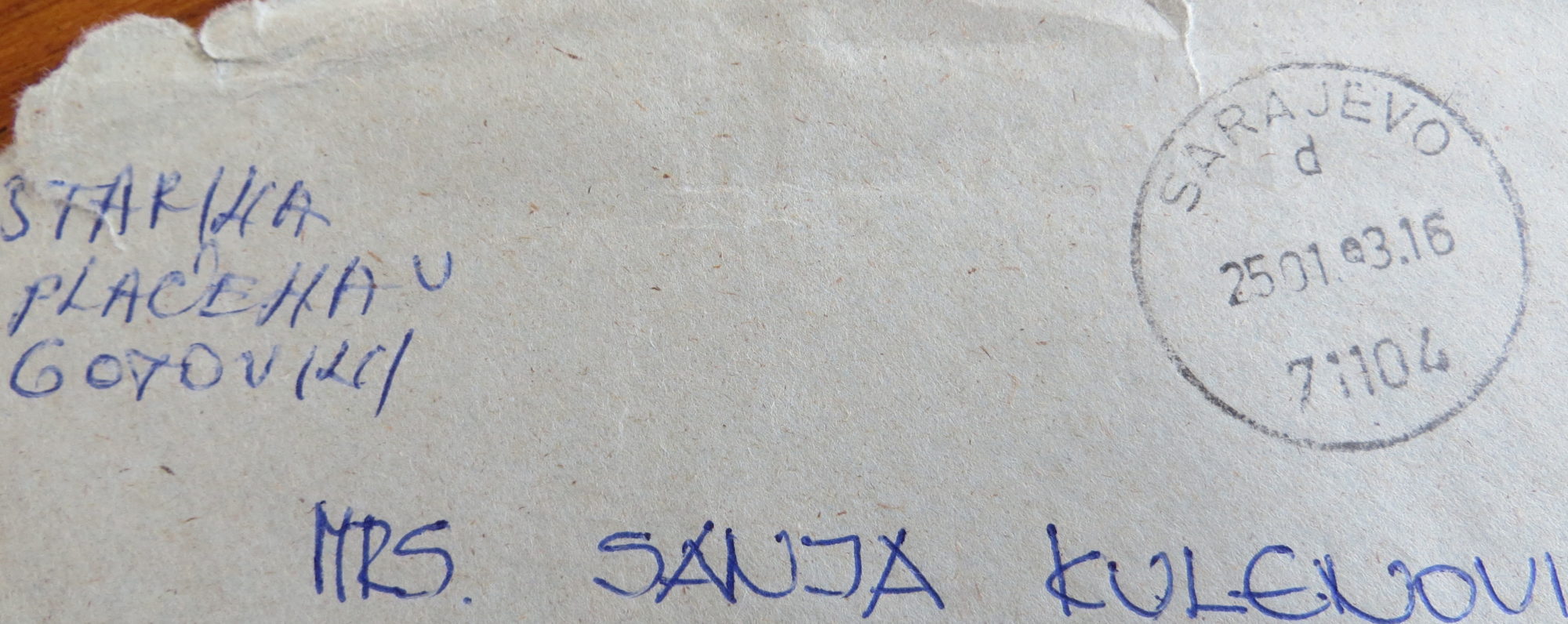

It was not meant to be a book, to begin with. It started about ten years ago, when I found a stack of letters my family and friends wrote to me from the besieged Sarajevo in the 1990s. My children were eleven and eight at the time and had no knowledge of the events that took place in the Balkans then, except that their “grandmas and grandpas lived through a war.” When I read them first bits and pieces, they looked at me with their teary eyes wide open and asked if it had happened “in real life”. The more I read to them, the more questions they asked, and I realized a had a job to do. I had to teach them what had happened in Sarajevo during the longest siege in modern history—and what better way to do it than by reading the words of those who experienced it.

I began organizing the letters by year and translating them into English, adding to them news clips and articles I had saved during the siege. Without even realizing, I created a unique historical document—but not the kind you would find by googling the Bosnian War. In my book, there are no armies, political sides or nationalities. There are people trapped in the city on one side and aggressors on the other.

“But, why did you come here in the first place? Why were we born here?”

These, of course, were valid questions, requiring more explanation, thus more writing. So I began adding parts of my diary to the material, and writing notes and stories of my own immigrant life in America. Little by little, almost ten years in the making, and the book was born.

Although Sarajevo’s siege was on prime-time news all over the world for years, it has now been largely forgotten. Bosnia is a small country far away, and a whole new generation was born after the siege ended more than twenty years ago. But, I believe the story of Sarajevo, however unique, is also universal. It is a story worth telling on so many levels; to celebrate unparalleled heroism, stoicism, and spirit that carried Sarajevans, my family included, through more than a thousand days of horror and prove that “something to live for” is always there and is worth fighting for; to preserve and treasure our heritage and prevent future urbicides from happening anywhere in the world; and, most of all, to deeply appreciate what we have in life, even small, “ordinary” things we often take for granted—for we never know when they might be out of our reach.