“Your uncle made it back to Sarajevo through the tunnel, which we now call ‘Sarajevo’s Metro’. Most of our food comes through the tunnel, too.” – From my parents’ letter, 1994.

“It was a top secret project, and it had to be a professional job. There could be no mistakes, as it would jeopardize the stability and safety of the airport. There were two starting points, from each side of the runway, thus digging direction had to be very accurate. The work began on January 28, 1993. Eight members of the civil protection unit worked 3-4 hours per day at the beginning. Bad weather conditions, lack of tools, constant shelling, among other problems, made the pace slow. Very few people believed the idea could work. Digging was completely manual; pickaxes and shovels were the only tools. The only light source was “kandilo”–a pot filled with oil and short fuse floating on it. Communication between two sides was nearly impossible as engineers had to risk their lives running across the runway.

By spring of 1993, miners joined the work, which was now being done in three shifts, twenty-four hours a day. Underground water had to be taken out manually, in buckets or canisters. On Dobrinja side, iron collected from Sarajevo factories was used to support the interior walls, as wood was hard to find. On Butmir side, however, iron was hard to find, so most material that was used was wood that came from mountain Igman. The excavated soil (2,800 cubic meters) was taken out in wheelbarrows and stored near the entrance.

On July 30, 1993, two men digging from two different sides managed to touch each other’s hand somewhere underneath Sarajevo airport. On that day, Sarajevo got a small path connecting it to the free territory. The tunnel was 800 meters long, and its average width was 1.5 meters.

At the beginning, everything was carried through the tunnel manually–food, oil, medication, ammunition, injured people…later, a small tram-line was installed along with small carts–at first, only 5-6 of them, but, due to sheer volume of material, 24 were made. The carts were not easy to push, especially because the tunnel had a few curves, and at one point dipped five meters below the surface, which is where the problem of underground water was the greatest. The tunnel was flooded to the ceiling twice.

On the average, twenty tons of materials were transported through the tunnel each night. The exits at either end had to be protected. Trenches were made so that people could safely enter the tunnel, but trucks had to approach the entrance without any headlights. Because of the oil shortage in the city, an oil pipeline was constructed through the tunnel, and later, telephone and electrical cables were placed as well. All the work was done at night, when civilians were not using the tunnel.”

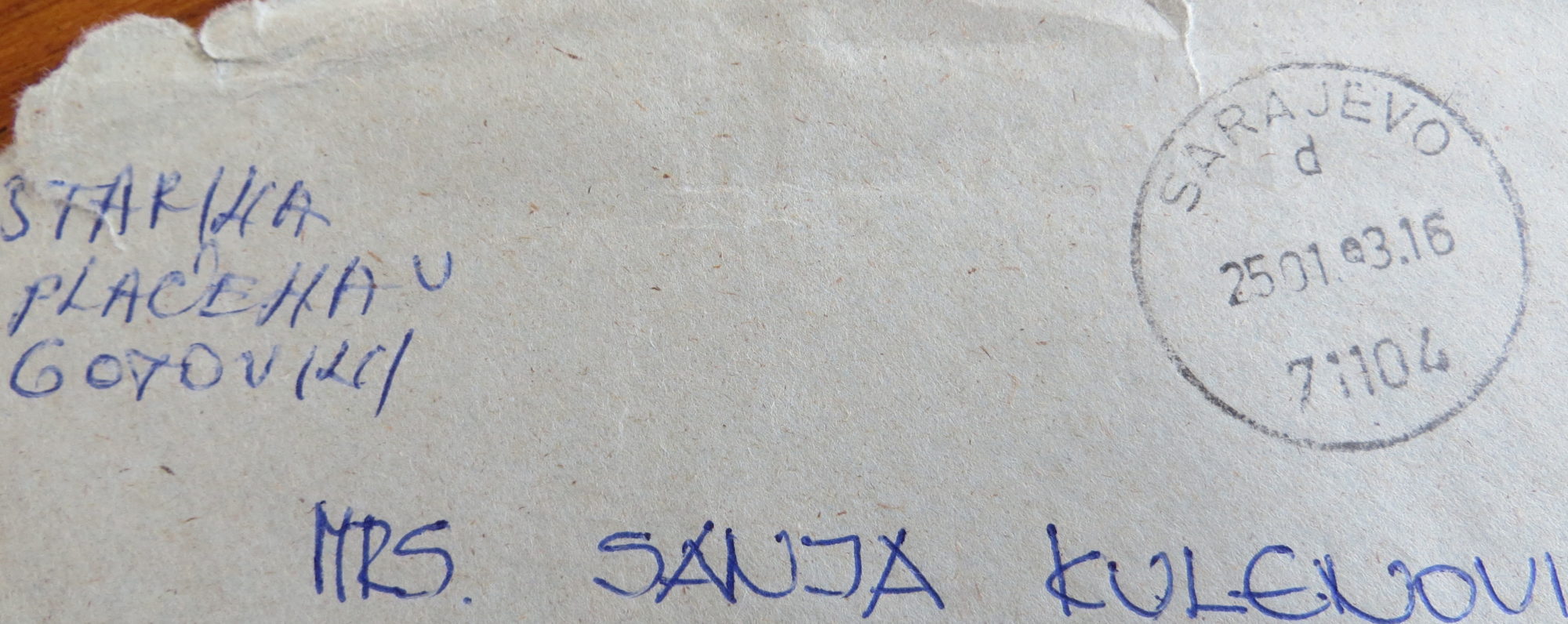

The above text is an excerpt from the brochure “Tunel” by Edis and Bajro Kolar, the owners of the house which was, in fact, the tunnel entrance. In 2010, when I came to see the tunnel, “grandma Sida” was still living there. She became well known to everyone who worked at the tunnel, as well as other passing through it. She would offer a glass of water for exhausted soldiers, a piece of bread for the hungry, and a small heated room in the winter time for people waiting for their turn.

After the siege ended and the airport was to be repaired, the tunnel had to be filled–all but the first twenty meters, which are now part of a small museum. Below are photos I took in 2010 when visiting it with my children.